Los Angeles Times photojournalist Luis Sinco’s photograph of Marine Lance Corporal James Blake Miller has become a contemporary iconic image in the tradition of Alberto Korda’s Che Guevara and Dorothea Lange’s Migrant Mother, Nipoma, California. Since it was taken in 2004, it has undergone numerous interpretations and become the rallying image of such disparate causes as American support for the war in Iraq, and the little-discussed effects of post-traumatic stress disorder in veterans. The image’s overt simplicity, as Sinco states, allowed Americans to identify with Miller in whatever manner they saw fit: “[P]eople love it because the subject’s face shows the full spectrum of emotions and they can pick and choose from any of them. The pro-war crowd saw patriotism. The anti-war crowd saw a damaged person” (Daum).

Korda’s portrait of the Argentine-Cuban revolutionary (“the most famous photograph in the world,” Goldberg, p. 156) provided the radical Left with a saintly image to rally around, and came to symbolize Third World movements in general. Lange’s Migrant Mother put a human face on the Great Depression and helped build support for political change. Sinco’s photograph, like Korda’s and Lange’s, encapsulates an entire historical event and in its simplicity leaves room for widely different interpretations and political manipulation.

Background

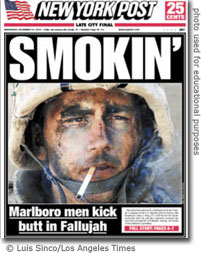

The “Marlboro Marine” photograph was taken by Luis Sinco in November of 2004, during the American assault on Fallujah. Sinco had been embedded with the 8th Marine Regiment’s Charlie Company, and for days endured heavy enemy fire alongside them, often seeking cover in abandoned buildings and mosques. Fallujah, a notoriously anti-American city with a deeply-entrenched religious history, proved to be one of the most difficult cities to subjugate, and numerous Americans as well as over a thousand Iraqi insurgents were killed in the earliest days of combat (Filkins).

Sinco and a few other Marines were located on a rooftop, resting after twelve straight hours of combat (including being pinned down in a traffic circle the night before by sniper fire). During the lull, James Blake Miller, 20 years old at the time, leaned against a wall and lit a cigarette. As he smoked he watched the sunrise, temporarily deafened by tank fire earlier in the day and unaware that the fighting, for the moment, had stopped. It was then that Sinco snapped the photo that would become the icon of American military intervention in Iraq:

“Miller’s camouflage war paint is smudged. He sports a bloody nick on his nose. His helmet and chin strap frame a weary expression that seems to convey the timeless fatigue of battle. And there is the cigarette, of course, drooping from the right side of his mouth in a manner that Bogart or John Wayne would have approved of. Wispy smoke drifts off to his left” (McDonnell).

Sinco, wary of using up his precious battery power, almost didn’t send the image to his editors, thinking they “would prefer images of fierce combat” rather than unknown Marines. He uploaded it as an afterthought, hardly expecting that it would grace the front pages of over 150 newspapers the very next day. The photograph of Miller – handsome, battle-weary, staring despondently out of the frame – resonated with American audiences and seemed to embody the struggle of the American soldier abroad. His anonymity (Sinco captioned the photo simply “A Marine”) reinforced the image’s strength, creating an aura of mystery around this Unknown Soldier who could be anyone’s son, brother, or husband (this, as we have read, also being one of the appealing aspects of the famous “Tank Man” image; by not having a specific identity, he potentially becomes any one of us).

Sinco, wary of using up his precious battery power, almost didn’t send the image to his editors, thinking they “would prefer images of fierce combat” rather than unknown Marines. He uploaded it as an afterthought, hardly expecting that it would grace the front pages of over 150 newspapers the very next day. The photograph of Miller – handsome, battle-weary, staring despondently out of the frame – resonated with American audiences and seemed to embody the struggle of the American soldier abroad. His anonymity (Sinco captioned the photo simply “A Marine”) reinforced the image’s strength, creating an aura of mystery around this Unknown Soldier who could be anyone’s son, brother, or husband (this, as we have read, also being one of the appealing aspects of the famous “Tank Man” image; by not having a specific identity, he potentially becomes any one of us).

Initial Reactions

David Perlmutter writes that “some pictures can be iconic without engendering outrage” (p. 11). Many of the photographs he writes about in Photojournalism and Foreign Policy sparked critical reactions from the American public upon their release (starving children in the Sudan, the curbside execution of a Viet Cong suspect, etc.). The portrait of Lance Corporal Miller is interesting because it became an icon overnight without initially engendering the “outrage” Perlmutter says is so common to these images. Normally when an image gains widespread notoriety, it is because it brings to light a subject or event which demands our indignation. “Marlboro Marine,” however, brings to mind our great political myths, appealing to our sense of patriotism – America is young (Miller was only 20), rebellious (the cigarette), and willing to make sacrifices for its ideals (the great anxiety evident in Miller’s face).

Most American newspapers chose to go with this initial optimistic interpretation. The New York Post in particular played heavily on the smoking imagery as symbolic of Miller’s cool, macho attitude. In his story “Hearts Burn for ‘Marlboro Man'”, Patrick Gallahue describes Miller as “a heartthrob to women everywhere and a hero in his hometown.” What are the first words we hear from the iconic Marine? “Tell Marlboro I’m down to four packs and I’m here in Fallujah till who knows when. Maybe they can send some. And they can bring down the price a bit” (Gallahue). These and other stories call to mind reporting from World War II, casting the young American soldier as a tough guy, not fazed by the excessive violence, or at least too proud to show it as a sign of weakness.

Most American newspapers chose to go with this initial optimistic interpretation. The New York Post in particular played heavily on the smoking imagery as symbolic of Miller’s cool, macho attitude. In his story “Hearts Burn for ‘Marlboro Man'”, Patrick Gallahue describes Miller as “a heartthrob to women everywhere and a hero in his hometown.” What are the first words we hear from the iconic Marine? “Tell Marlboro I’m down to four packs and I’m here in Fallujah till who knows when. Maybe they can send some. And they can bring down the price a bit” (Gallahue). These and other stories call to mind reporting from World War II, casting the young American soldier as a tough guy, not fazed by the excessive violence, or at least too proud to show it as a sign of weakness.

The Pentagon in particular picked up on the image and made Miller a poster boy for the war effort. “‘That’s a great picture,’ echoed Col. Craig Tucker, who heads the regimental combat team that includes Miller’s battalion. ‘We’re having one blown up and sent over to the unit'” (McDonnell). Righteous anger over the Eddie Adams execution photograph helped turn public opinion against the Vietnam War; images of starving Somalis led to philanthropic intervention in the early ’90s; Sinco’s photograph caused no such major policy changes. Rather, viewers sent Miller cartons of Marlboros and admiring letters. President Bush sent cigars and White House memorabilia. Having become an icon of the war and a minor celebrity back home, Miller was offered an early ticket home – he flatly refused (“Miller hesitated, then shook his head. He did not want to leave his buddies behind” [Sinco]), adding to his already heroic reputation.

Changing Perceptions of the Icon

Because of the photograph’s rapid dissemination among the American public and its subsequent popularity (“The image, printed in more than 100 newspapers, has quickly moved into the realm of the iconic” [McDonnell]), there was little opportunity to discuss the context in which it was taken, as well as the reality behind the iconic face. As already stated, this anonymity is largely what made the image so popular; Miller became an Everyman of the Armed Forces. Yet public interest in the photo’s subject caused Sinco (and various other correspondents) to track down the Marine for a follow-up story.

These early stories, such as the Gallahue piece, portrayed Miller as the “macho bad-ass American Marine in Iraq” (Ludtke); they reinforced the notion that the photo had already created amongst many viewers. Once Miller shed his anonymity, however, the real experience of the American Marine in Iraq quickly became evident. This is noticeable in later news coverage of Miller. Let us take, for example, differing descriptions of the moment in which the photo was taken. In McDonnell’s story from November 13, 2004, Miller casually plays off the significance of the moment:

“‘I just don’t understand what all the fuss is about,’ Miller drawls Friday as he crouches inside an abandoned building with his platoon mates, preparing to fight insurgents holed up in yet another mosque. ‘I was just smokin’ a cigarette and someone takes my picture and it all blows up'” (McDonnell).

This differs drastically from a description written two years later, in the Los Angeles Times:

“His detached expression in the photo seemed to signify different things to different people – valor, despair, hope, futility, fear, courage, disillusionment. For Blake, the photograph represents a pivotal moment in his life: an instant when he feared he would never see another sunrise, and when his psychological foundation began to fracture” (Zucchino).

The difference between casually smoking a cigarette and contemplating ones’ mortality is as vast as the difference between early and later interpretations of the “Marlboro Marine” photo. The man who became overnight the symbol of America’s determination to “get the job done” in the Middle East became the reluctant spokesman for post-traumatic stress disorder. Every aspect of Miller’s life that was seen as typically “American” and endeared so many readers to him gradually unraveled with time: he and his high school sweetheart separated and eventually divorced; barred from the law enforcement job he had intended to pursue because of his PTSD, he ended up joining a criminally-suspect motorcycle gang; he now collects disability checks and lives in a trailer behind his father’s house, and has come close to committing suicide on numerous occasions. All of these facts about Miller’s life have influenced how we now look at Sinco’s “Marlboro Marine.”

Conclusions

Perlmutter argues in his book that a politician’s handling of and response to iconic images determines how they ultimately affect foreign policy. For example, if Lyndon B. Johnson had applauded General Loan as an example for all other South Vietnamese officers to follow, the Eddie Adams photograph may have become a symbol of the pro-war movement. The Marine Corps elites tried to make “Marlboro Marine” an inspiring image to boost troop morale, but Miller’s own outspokenness and the persistence of journalists like Luis Sinco to expose the truth behind the image resulted in a drastic shift in the interpretation of the photograph. Lange’s Migrant Mother and Korda’s Che Guevara meant different things to different people, but the historical context in which they were taken decided how they were ultimately received by the public (Che remains a saint rather than a criminal; the migrant mother becomes a Madonna-like figure of the downtrodden). In due time, “Marlboro Marine” will also become a defining image of an era; whether it will symbolize American determination or the grim effects of a foolhardy war remains to be seen.

Works Cited

-

Sinco, Luis. “Media Storm: “The Marlboro Marine”.” http://mediastorm.org/0020.htm

- Sinco , Luis. “Two lives blurred together by a photograph.” The Los Angeles Times. http://articles.latimes.com/2007/nov/11/nation/na-marlboro1

- Sinco , Luis. “Rescue operation aims to save a wounded warrior.” The Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com/news/nationworld/nation/la-na-marlboro12nov12,0,4839662.story

- Gallahue, Patrick. “Hearts Burn for ‘Marlboro Man’.” The New York Post. http://www.nypost.com/p/news/hearts_burn_for_marlboro_man_4SqKqSIqob04opdrXlM5GP

- Gallahue, Patrick. “Marlboro Marine Fires Up Troop Morale.” The New York Post. http://www.nypost.com/p/news/marlboro_marine_fires_up_troop_morale_I2eDrf29m29p5pMDKL2lXP

- Starr, Michael. “Marlboro Marine Tells His War Story.” The New York Post. http://www.nypost.com/p/entertainment/tv/marlboro_marine_tells_his_war_story_uhyJMN2oCaZcAXkCU1iLQL

- McDonnell, Patrick J.. “Marine Whose Photo Lit Up Imaginations Keeps His Cool.” The Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com/news/nationworld/nation/marlboromarine/la-na-marlboroman-mcdonnell11nov11,0,6621414.story

- Zucchino , David. “Iconic Marine Is At Home But Not At Ease.” The Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com/news/nationworld/nation/marlboromarine/la-na-marlboroman-zucchino11nov11,0,4949709.story

- Daum, Meghan. “Picture Imperfect.” The Los Angeles Times. http://www.latimes.com/news/printedition/asection/la-oe-daum17nov17,0,47452.column

- Ludtke, Melissa. “A Different Approach to Storytelling.” Nieman Reports. http://www.nieman.harvard.edu/reportsitem.aspx?id=102095

I do not own the rights to any of the photographs used here.